__________________________________________________

Narrative Cinema

Narrative filmmaking refers to the types of movies that tell a story. These are the films most widely screened in theatres, broadcast on TV, streamed in the internet, and sold as DVDs and Blu-rays. Though fictional filmmaking is another term for narrative cinema, the word “fictional” doesn’t imply that such movies are purely based on fictive events. In some cases, veracity and creation blend together.

One of the storylines in James Cameron’s Titanic, for instance, pertains the steamship RMS Titanic that struck an iceberg in her maiden voyage and sunk soon afterwards – a real, greatly documented incident that happened on April 14, 1912. However, the romance between Rose and Jack, another prominent storyline in the movie, is a product of Cameron’s imagination, just like both characters.

The terms “fictional cinema” and “narrative cinema” carry the understanding that the filmmaker has the freedom to create storylines and alter historical facts as he or she sees fit. This freedom allows the director to shape the movie and perfect the story. One of the many reasons why Titanic broke a box office record was because the audience could identify with Jack and Rose and root for them.

The Classic Structure of Narrative Films

Fictional films are composed by a string of events and structured based on cause and effect. While the beginning of a movie and the introduction of certain characters are always arbitrary, the subsequent scenes, all the way to dénouement, must happen for a clear reason; an identifiable motivation that justifies character behavior, action, and goals. The occurrences in narrative cinema are never random; rather, they are always organized based on a main line of action and connected through theme.

In The Shawshank Redemption (1994), when Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) is convicted of a crime he didn’t commit and unfairly incarcerated (cause), he begins to plan his escape (effect).In Tootsie (1981), when Michael Dorsey (Dustin Hoffman) is confronted by his agent who says that he will never find job in show business, Michael decides to dress up as woman and prove that he is a great actor worthy of major roles, regardless of his gender.

The structure of narrative cinema draws heavily on the 3-act structure and character arc of ancient Greek dramaturgy.

____________________________________

Experimental Film

Also known as avant-garde, experimental films are rare and totally unpopular. Some people may spend their entire lives without ever catching a glimpse of an experimental movie. Most will never sit through one.

As the word “experimental” suggests, this type of movie is trying something new, different...so different that, at first, it will cause confusion, if not annoyance on the viewer.

In simple terms, experimental films are incredibly easy to define but quite difficult to understand since most people have no preconception of what they are. Imagine a movie that is neither narrative nor documentary. What remains? Chaos, disorder, incoherence … An amalgam of ideas forced together by the filmmaker without any regards for characters, structure, or theme.

The vast majority of avant-garde films are not screened in theatres, aired on TV, or sold in discs – they are not mainstream and have no commercial life whatsoever.

So who makes them and why?

Like any other art form, cinema can also be a therapeutic activity. This is not to imply that those who make them are ill or demented, not at all. However, some directors are not concerned about what people may think or commercial success – they make movies for themselves.

Occasionally, an experimental movie may become popular despite its peculiarities or even because of them. Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel achieved quite some renown with Un Chien Andalou (The Andalusian Dog). A surrealist, 16-minute movie from 1928, Un Chien Andalou is generally considered the most famous experimental movie. Here goes the first minute…

Un Chien Andalou opens with a title card that reads “Once upon a time,” followed by a tight shot of a razor being sharpened. After sharpening his razor, a man (played by Buñuel himself) walks to a balcony, from where he gazes at the moon, which is about to be obscures by a thin passing cloud. Then there’s a close-up of young woman, who sits calmly at the balcony. The man looks at the moon again, and, as he looks back at the woman, he slits her eye. End scene. Another title card: “Eight years later.” Another man bicycles down a street while wearing a nun’s habit…

Again, experimental films are not imprisoned by story structure, character arc, or common sense.

________________________________________

Content;

WHAT IS DIGITAL CONTENT?

In its broadest term, digital content refers to data (video, written, information) that can be viewed on a digital platform. Within the spectrum of filmmaking, digital content refers to the variety of film or video content generated for specific online use. Free digital content can be accessed by anyone with a computer, tablet or mobile phone. YouTube and the television networks all have online outlets that can be viewed for free and streamed as real time or downloads. There are also online subscription services that provide access to a host of films and television programs for a nominal payment each month.

This has become such a popular way to view content that Amazon and Netflix now output their own productions, attracting talent from the film and television industry to work on their original content. Amazon’s Amazon Studios operate their film and original series development, with filmmakers from around the globe contributing ideas in the hope of a development deal. Amazon operates an open door policy with the aim of providing feedback in 45 days; anyone can apply. Their shows such as Man in the High Castle, Transparent and Mozart in the Jungle have received critical praise, and viewing figures some broadcast stations could be envious of. Netflix original series Orange is the new Black, and House of Cards have also been lauded as compelling original productions, attracting A-list talent on both sides of the camera.

The meteoric rise of branded content and content marketing has seen a significant shift in the work of the creative agencies and corporate production companies. Companies realised they could reach out to their customers in a personal and engaging way using online commercials and content created specifically for their market. Video content creators are in high demand, primarily produced by corporate and commercials companies who understand the how to output a message using creative media, new start-ups are entering the marketplace regularly and the trend has shown no sign of slowing down. The Dollar Shave Club is an example of one of the most effective forms of a film for content marketing to date, their ‘advert’ going viral with 4.7 million views in the first three months from shares on social media. After 48 hours on YouTube, the company had 12,000 new subscribers, which crashed their servers and had them advertising for a logistic manager. Alongside a few adverts on Google, this was the only marketing output costing $4,500.

The concept of webisodes, or if you are using your phone to access - mobisodes, started in 1995. They refer to a repeated web series as an alternative to TV, featuring A-list talent (producing similar content with a significant reduction in cost) and by brands who seek to engage their consumer base through active web content and social media. YouTube has been the natural home for webisodes, Steve Coogan's Mid-morning Matters, Mike O’Brian's 7 minutes of Heaven and Jerry Seinfield's Comedians in cars getting coffee, have all been immensely successful web series, producing multiple episodes of only 4 - 7 minutes in length.

WHO MAKES DIGITAL CONTENT

Digital content is made by a host of companies such as corporate video companies, broadcasters, independent production companies, some commercial enterprises and newly formed start-ups. Online subscription VOD companies such as Amazon, Hulu and Netflix make their own original drama.

HOW MUCH DOES DIGITAL CONTENT COST TO MAKE?

Overheads for digital content are relatively low compared to other mediums in the creative industries. Due to the change in technology and relatively cheap to buy/hire camera equipment you can make filmic, high-quality productions without employing a full film crew. The drama series output by the VOD companies operate on another level; House of Cards reportedly cost over $100 million for 13 episodes.

WHAT CREW IS INVOLVED?

See feature films when looking for crew on original VOD drama series. Drama being produced in this capacity is treated very much like a TV drama, or a feature film. Previous to the rise of online programming, TV drama in the UK and US began to attract a host of A-list talent to the small screen. Scripts and series have evolved, and the long run of work gave actors a chance to explore their characters over years, rather than months.

If working for a production company producing a web series, the crew become more refined as the budget will not be as sizeable as the VOD companies

WHO HIRES THE CREW?

Currently, the VOD studios are based in the US, but they do have publicity branches in the UK. Production managers at production companies are the most likely people to hire when crewing up for specific productions. If you are looking for office junior positions look for the office manager at larger companies.

___________________________________________________

Animation;

Animated Films are ones in which individual drawings, paintings, or illustrations are photographed frame by frame (stop-frame cinematography). Usually, each frame differs slightly from the one preceding it, giving the illusion of movement when frames are projected in rapid succession at 24 frames per second. The earliest cinema animation was composed of frame-by-frame, hand-drawn images. When combined with movement, the illustrator's two-dimensional static art came alive and created pure and imaginative cinematic images - animals and other inanimate objects could become evil villains or heroes.

Animations are not a strictly-defined genre category, but rather a film technique, although they often contain genre-like elements. Animation, fairy tales, and stop-motion films often appeal to children, but it would marginalize animations to view them only as "children's entertainment." Animated films are often directed to, or appeal most to children, but easily can be enjoyed by all. See section on children's-family films.

Also see this website's related sections on Pixar-Disney Animations, Visual and Special Effects Milestones in Cinematic History as well as AFI's 10 Top 10 - The Top 10 Animated Films.

The History of Animation;

Early Animation:

The inventor of the viewing device called a praxinoscope (1877) , French scientist Charles-Emile Reynaud, became known as the First Motion Picture Cartoonist. He had created a large-scale system called Theatre Optique (1888) (aka "optical theatre") which could take a strip of pictures or images and project them onto a screen. He demonstrated his system in 1892 for Paris' Musee Grevin - it was the first instance of projected animated cartoon films (the entire triple-bill showing was called Pantomimes Lumineuses), with three short films (each approx. 10-15 minutes in length) that he had produced, in order:

| Title Screen | Title (Year) | Notes |

| Un Bon Bock (1888) (A Good Beer) 15 minutes in length | (700 individually, hand-painted frames) | |

| Le Clown et Ses Chiens (1890) (The Clown and His Dogs) 10 minutes in length | (300 individually, hand-painted frames) | |

| Pauvre Pierrot (1891) (Poor Pete) 15 minutes in length |  the only surviving example (500 individually, hand-painted frames) |

To create the animations, individually-created images were painted directly onto the frames of a flexible strip of transparent gelatine (with film perforations on the edges), and run through his projection system. Depending upon one's definition of terms, some consider Pauvre Pierrot the oldest-surviving animated film ever made and publically broadcast.

The predecessor of early film animation was the newspaper comic strips of the 1890s, in which each cartoon box was similar to a film frame. Some of the earliest animated films used very primitive stop-motion techniques (known as 'stop-trick' or 'substitution splice'), when a single change was made to an object between two shots. This early technique has been termed stop-motion substitution or stop-action.

Pioneering animators, directors, and filmmakers Albert E. Smith and newspaper cartoonist James Stuart Blackton, both co-founders of the Vitagraph Company, created The Humpty Dumpty Circus (1898), a presumed lost film. This theatrical 'cartoon' from Vitagraph, a lost silent film, was claimed by Guinness to be "the first animated film using the stop-motion technique to give the illusion of movement to inanimate objects." And in Arthur Melbourne Cooper's public service announcement Matches: An Appeal (1899, UK), animation was achieved by stop-trick images of moving matchsticks. One matchstick wrote an appeal on a blackboard, requesting that Britishers send matches (which were once somewhat expensive) to soldiers fighting in the Boer War.

Newspaper cartoonist J. Stuart Blackton also produced the live-action The Enchanted Drawing (1900), a Vitagraph Studios short film that featured a drawn character and some objects. It contained one of the earliest surviving prototypes of stop-action animation (non continuous frame-by-frame filming). In one of the earliest sequences of 'trick' animation, it showed a chalk-talk artist (Blackton himself) using a large stand-up easel on which he drew a round cartoon face of an elderly man. He then sketched a bottle of wine and a glass goblet in the upper-right hand corner of the page - and then removed the two items from the sketch paper, holding them up as real 3-D objects and pouring himself a glass of wine. He did the same with the man's hat and cigar. At the conclusion of the short segment, he then restored all the elements back into the picture.

In Edwin S. Porter's Fun in a Bakery Shop (1902), the Edison director molded clay sculptures and filmed with stop-action animation, thereby creating the first known primitive example of stop-motion clay animation. The 80-second film was a combination of stop-action photography and "trick" object manipulation. In the short utilizing a technique known as "lightning sculpting," a baker's assistant sculpted dough thrown onto the side of a flour barrel, making various faces and comical shapes - executed with smooth edits between stop-camera "freezes."

|  |  |

|  |  |

A more ambitious breakthrough in the step-crank process (frame-by-frame animation, the precursor of stop-motion) was in Segundo de Chomón's comedy-fantasy short for Pathe Frères films, titled The Electric Hotel (1905, Sp.) (aka El Hotel Electrico). It was released in the US in 1908. It was a trick film similar to the films of Georges Melies (hence, Chomon was dubbed "the Spanish Melies"). [Note: He was also credited with developing "the dolly" (a camera on rails that 'traveled' for tracking shots).] The two characters in the short were the director and his wife Julienne Mathieu, who played couple Bertrand and Laure arriving at a totally-automated hotel. Once the two checked in, their luggage went into motion and completely unpacked itself upstairs. Electrical switches in their room automatically performed various tasks: shoe-brushing and shining, hair-combing and beard-shaving, and letter-writing. But then in its cautionary ending about modern technology, the machinery behind all of the hotel's automation malfunctioned when a control room technician pulled the wrong lever, and everything was chaotically jumbled in their hotel room.

Historically and technically, the first animated film (in other words, the earliest animated film ever printed on standard motion-picture film) was Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906), also made by J. Stuart Blackton. It was the earliest surviving example of a drawn animated film. It was the first cartoon to use the single frame method, and was projected at 20 frames per second. In the film, a cartoonist's line drawings of two faces were 'animated' (or came to life) on a blackboard. The two faces smiled and winked, and the cigar-smoking man blew smoke in the lady's face; also, a circus clown led a small dog to jump through a hoop. Also, Blackton's stop-motion The Haunted Hotel (1907) was one of the first examples of animation (stop-motion mixed with live-action) that became exceedingly well-known. Its main sequence of objects coming to life on a rural country inn's dinner table baffled viewers (and the bewildered, long-nosed main character!) as to how the special effect was accomplished.

This was soon followed by the first fully-animated film (without live action) - Emile Cohl's Fantasmagorie (1908, Fr.), using traditional animation techniques. It consisted solely of simple line drawings (of a clown-like stick figure) that blended, transformed or fluidly morphed from one image into another.

Winsor McCay ("America's Greatest Cartoonist"):

New York Herald comic-strip animator and sketch artist Winsor McCay (1869-1934) produced a string of comic strips from 1904-1911, his three best being Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend, Little Sammy Sneeze, and Little Nemo in Slumberland (from October 15, 1905 to July 23, 1911). Although McCay wasn't the first to create a cartoon animation, he nonetheless helped to define the new industry. He was the first to establish the technical method of animating graphics. His first animation attempt used the popular characters from his comic strip (and became part of his own vaudeville act): Little Nemo in Slumberland (1911) (with 4,000 hand-drawn frames), followed by How a Mosquito Operates (1912) (with 6,000 frames).

New York Herald comic-strip animator and sketch artist Winsor McCay (1869-1934) produced a string of comic strips from 1904-1911, his three best being Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend, Little Sammy Sneeze, and Little Nemo in Slumberland (from October 15, 1905 to July 23, 1911). Although McCay wasn't the first to create a cartoon animation, he nonetheless helped to define the new industry. He was the first to establish the technical method of animating graphics. His first animation attempt used the popular characters from his comic strip (and became part of his own vaudeville act): Little Nemo in Slumberland (1911) (with 4,000 hand-drawn frames), followed by How a Mosquito Operates (1912) (with 6,000 frames).

His first prominent, successful and realistic cartoon character or star was a brontosaurus named Gertie in Gertie the Dinosaur (1914) (with 10,000 drawings, backgrounds included), again presented as part of his act. In fact, McCay created the "interactive" illusion of walking into the animation by first disappearing behind the screen, reappearing on-screen!, stepping on Gertie's mouth, and then climbing onto Gertie's back for a ride - an astonishing feat! It was the earliest example of combined 'live action' and animation, and the first "interactive" animated cartoon. Some consider it the first successful, fully animated cartoon - it premiered in February 1914 at the Palace Theatre in Chicago.

|  |

McCay's 12-minute propagandistic, documentary-style The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918), an animation landmark, was the first serious re-enactment of an historical event - the torpedoing of the RMS Lusitania by a German U-boat on May 7, 1915, resulting in the loss of almost 2,000 passengers. It was one of the earliest films to utilize cel animation.

Soviet animator (W)ladislaw Starewicz created the first 3-D, stop-motion narratives in two early films with animated insects: The Grasshopper and the Ant (1911) and The Cameraman's Revenge (1911). And John Randolph Bray's first animated film, The Artist's Dream(s) (1913) (aka The Dachshund and the Sausage), the first animated cartoon made in the U.S. by modern techniques was the first to use 'cels' - transparent drawings laid over a fixed background.

Felix the Cat: The Most Successful Cartoon Character During the Silent Era

The first animated character that attained superstar status (and was anthropomorphic) during the silent era was the mischievous Felix the Cat, in the studios of Pat Sullivan, Felix's character cartoon owner. Supposedly, Felix was inspired by Rudyard Kipling's "The Cat That Walked By Himself" in the Just So Stories for Little Children published in 1902. Felix was not the most lucrative of the silent animated cartoon series, nor the longest-running, and did not come from a major studio.

The first animated character that attained superstar status (and was anthropomorphic) during the silent era was the mischievous Felix the Cat, in the studios of Pat Sullivan, Felix's character cartoon owner. Supposedly, Felix was inspired by Rudyard Kipling's "The Cat That Walked By Himself" in the Just So Stories for Little Children published in 1902. Felix was not the most lucrative of the silent animated cartoon series, nor the longest-running, and did not come from a major studio. Felix was the first unique and original animated star to be created specifically for the screen - he wasn't derived from the comics or some other source, although he retained remarkable similarities to Charlie Chaplin's "Little Tramp." Felix originated in Pat Sullivan's studio (Sullivan took all the credit), but was drawn and designed by young animator Otto Messmer. For the first few years from 1919 to 1921, the Felix cartoons (25 of them) were distributed as shorts by Paramount Pictures, and then by Margaret J. Winkler (64 films from 1922-1925), the first female to produce and distribute animated films. From 1925 to 1928 (a total of 78 cartoons), distribution was handled by Educational Pictures, a film distribution company, and then First National Pictures took over distribution from 1928–1929.

Felix was the first unique and original animated star to be created specifically for the screen - he wasn't derived from the comics or some other source, although he retained remarkable similarities to Charlie Chaplin's "Little Tramp." Felix originated in Pat Sullivan's studio (Sullivan took all the credit), but was drawn and designed by young animator Otto Messmer. For the first few years from 1919 to 1921, the Felix cartoons (25 of them) were distributed as shorts by Paramount Pictures, and then by Margaret J. Winkler (64 films from 1922-1925), the first female to produce and distribute animated films. From 1925 to 1928 (a total of 78 cartoons), distribution was handled by Educational Pictures, a film distribution company, and then First National Pictures took over distribution from 1928–1929.

The characer didn't start out as "Felix." The (unnamed) cat's first two cartoons, when Felix was known only as "Master Tom" (and was a resident of Pussyville) were Feline Follies (1919) (Felix's debut short film) and Musical Mews (1919), considered lost. Both films were Paramount Screen Magazine cartoons, a semi-weekly compilation of short film segments that included animated cartoons. Initially a one-shot character, Felix was included with two other cartoons as part of the Paramount Screen Magazine program, so there were no ending titles. By the third Felix cartoon, The Adventures of Felix (1919), Felix took his permanent name. The character instantly became popular and his own stand-alone cartoon series was immediately launched.

|  |  |

Messmer directed and animated more than 150 Felix cartoons in the years 1919 through 1929. Felix in Hollywood (1923) was notable as the first (or earliest) animated cartoon to feature cameos and caricatures of Hollywood celebrities (Felix appeared alongside Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, Gloria Swanson, Ben Turpin, William S. Hart, and even film censor William Hays and director Cecil B. DeMille).

At the same time, Messmer (and others) started a Felix comic strip in 1923 (debuting in England's Daily Sketch on August 1, 1923) that was soon distributed in the US by King Features Syndicate - the strip continued in various forms until 1966. Felix was the first character to be so ubiquitous and widely merchandised - in syndicated comic strips, songs, and consumer products. Originally, Felix appeared as an angular, snout-nosed cartoonish fox, but by 1924, Felix's appearance (by animator Bill Nolan) was made rounder and cuter, more smooth-moving and wide-eyed, as seen in Felix the Cat Trips Thru Toyland (1925), and one of his last big cartoons was Felix in Jungles Bungles (1928). The last Felix the Cat silent cartoon distributed by Educational Pictures was The Last Life (1928), at the time of the advent of the talkies and the success of Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse.

First Color Cartoon:

It has been difficult to decisively determine the first color cartoon, since most of the top contenders are lost films, and it depends on how the term "color" or "animated" is defined:

| Some sources claim that the Natural Colour Kinematograph Company's In Gollywog Land (1912, UK), a lost film, was the earliest color animation, using Kinemacolor (a two-color process). It was essentially a live-action film with puppet-animated sequences. | |

| Producer John Randolph Bray's (and Bray Picture Corporation's) The Debut of Thomas Cat (1920) (aka The Debut of Thomas Katt) has often been credited as the first color cartoon made in the US, using the expensive Brewster Natural Color Process (a two-emulsion subtractive color process), an unsuccessful precursor of Technicolor. It was the first animated short genuinely made in color using color film. Drawings were made on transparent celluloid and painted on the reverse, then photographed with a two-color camera. | |

| Another contender for the world's first color cartoon was Vance DeBar "Pinto" Colvig's self-produced Pinto’s Prizma Comedy Revue (1919), made with the two-color Prizma color system. | |

Fiddlesticks (1930) | MGM's and ex-Disney animator Ub Iwerks' debut short Fiddlesticks (1930)was the first animated film released using the two-strip Technicolor process. It was notable as the first Flip the Frog cartoon for MGM, and one of only two made in color. It was also the first complete animated short to combine color and synchronized sound. |

First Animated Feature:

The little-known but pioneering, oldest-surviving feature-length animated film that can be verified (with puppet, paper cut-out silhouette animation techniques and color tinting) was released by German film-maker and avante-garde artist Lotte Reiniger, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (aka Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed) (1926, Germ.), based on the stories from the Arabian Nights. Reiniger's achievement is often brushed aside, due to the fact that the animations were silhouetted, used paper cut-outs, and they were done in Germany. And the rarely-seen prints that exist have lost much of their original quality. However, the film was very innovative -- it used multi-plane camera techniques and experimented with wax and sand on the film stock.

The little-known but pioneering, oldest-surviving feature-length animated film that can be verified (with puppet, paper cut-out silhouette animation techniques and color tinting) was released by German film-maker and avante-garde artist Lotte Reiniger, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (aka Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed) (1926, Germ.), based on the stories from the Arabian Nights. Reiniger's achievement is often brushed aside, due to the fact that the animations were silhouetted, used paper cut-outs, and they were done in Germany. And the rarely-seen prints that exist have lost much of their original quality. However, the film was very innovative -- it used multi-plane camera techniques and experimented with wax and sand on the film stock.

Early Walt Disney: The Laugh-O-Gram Studios, the Alice Comedies, and Oswald the Rabbit

A classic animator in the early days of cinema was Walt Disney, originally an advertising cartoonist at the Kansas City Film Ad Company, who initially experimented with combining animated and live-action films. The very first films were made by him (and other animators) at his own animation studio in Kansas City (Missouri), known as the Laugh-O-Gram Studios. Among his employees were several pioneers of animation: Ub Iwerks, Hugh Harman, Rudolf Ising, Carmen Maxwell, and Friz Freleng. They created short cartoons (live-action with some animation) - obviously named Laugh-O-Grams, such as Little Red Riding Hood (1922) - the first"real" Walt Disney cartoon, followed by The Four Musicians of Bremen (1922). The cartoons were shown in Kansas City's Newman Theatres. There were seven original Laugh-O-Grams fairy tales in 1922, all of which have survived.

While still at the failing Laugh-O-Gram Studios, Disney's staff made the first Alice Comedy, a one-reel (ten-minute) short subject pilot titled Alice's Wonderland (1923). Disney's Alice cartoons placed a live-action title character (Alice) into an animated Wonderland world.

|  |  |  |

After bankruptcy in 1923, Disney was forced to relocate and set up his own studio in Los Angeles (the Disney Brothers Studio). He continued his work on the Alice Comedies (or Alice in Cartoonland). These were Disney's first successful silent live-action/animated cartoons (from 1923-1927) - a series of shorts (composed of 56 episodes) that continued with Alice's Day at Sea (1924).

Soon after, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit (designed by Disney's chief animator Ub Iwerks) became Disney's first successful animal mascot or star in a cartoon series distributed by Universal. It was Disney's third animated series, following the Laugh-O-Grams and Alice Comedies (see above), when he was forced to compete with Felix the Cat and Koko the Clown. Oswald appeared in 27 silent, black and white cartoon shorts (from 1927-1928 for Universal Studios), such as Poor Papa (1927) (Oswald's debut pilot film, but not released until 1928), and Trolley Troubles (1927) (the first official released short, but produced second). Oswald was also the firstDisney character to be merchandized.

|  |  |

Universal/Disney/Winkler | ||

In 1928, Disney was forced to give up the character of Oswald to George Winkler Productions, and then to Universal and the Walter Lantz Studios, where another up-and-coming animator Tex Avery was working (see more on Avery later). Oswald the Lucky Rabbit's first sound cartoon was Hen Fruit (1929) (a lost film), while the first Oswald short produced by Walter Lantz/Universal was Race Riot (1929).

The Debut of Disney's Mickey Mouse:

Disney moved onto another memorable character - first named Mortimer Mouse - or Mickey Mouse (looking like Oswald with his ears cut off) in 1928. In 1928, Disney Studios' chief animator Ub Iwerks developed a new character from a figure known as Mortimer Mouse, a crudely-drawn or sketched, rodent-like 'Mickey Mouse' - slightly similar to Felix the Cat. [Note: Mickey Mouse was never a comic strip character before he became a cartoon star.]

Disney moved onto another memorable character - first named Mortimer Mouse - or Mickey Mouse (looking like Oswald with his ears cut off) in 1928. In 1928, Disney Studios' chief animator Ub Iwerks developed a new character from a figure known as Mortimer Mouse, a crudely-drawn or sketched, rodent-like 'Mickey Mouse' - slightly similar to Felix the Cat. [Note: Mickey Mouse was never a comic strip character before he became a cartoon star.]

The first Mickey Mouse cartoon to be released (as a pilot test screening only on May 15, 1928) was Plane Crazy (1928), in which Mickey (without his trademark shoes or gloves), while impressing Minnie, imitated aviator Charles Lindbergh. The second was Steamboat Willie (1928) (first released as a silent film on a limited basis on July 29, 1928), with Mickey as a roustabout on Pegleg Pete's river steamer, again without his trademark white gloves. The third was The Gallopin' Gaucho (1928) (although the second film to be produced) with a silent version completed on August 2, 1928 (but not released until after Steamboat Willie). And the fourth was The Barn Dance (1929), first released on March 14, 1929.

(These early films were soon re-worked and re-released with sound - with electrifying results. For example, Plane Crazy (1928) was again released as a sound cartoon on March 17, 1929, and Steamboat Willie (1928) was theatrically re-released on November 18, 1928 with sound, and premiered at the 79th Street Colony Theatre in New York.)

|  |  |  |

To help make Mickey stand out from other cartoon characters at the dawn of the talkies, the 7-minute Steamboat Willie (1928) was re-released in a sound version - it was the first cartoon with post-produced synchronized soundtrack (of music, dialogue, and sound effects) and is considered Mickey Mouse's screen debut performance and birthdate. Animated star Mickey (with Minnie) was redrawn with shoes and white, four-fingered gloves. [The character was a take-off based upon Buster Keaton's Steamboat Bill (1928). ] It was a landmark film and a big hit - the first sound cartoon to be a major hit - leading to many more Mickey Mouse films during the late 1920s and 1930s.

Strangely, Mickey's first sound cartoon didn't include Mickey's voice -- he didn't speak until his ninth short, The Karnival Kid (1929)when he said the words: "Hot dogs!" [Note: Walt's voice was used for Mickey.] Walt Disney was fast becoming the most influential pioneer in the field of character-based cel animation, through his shrewd oversight of production.

Dinner Time (1928) | At about the same time, the first publically-shown 'synchronized' sound-on-film cartoon released theatrically was Dinner Time (1928). The cartoon was directed by Paul Terry - his first sound cartoon for Fables Studios, as part of an Aesop's Film Fables series. It was notable for being among the first cartoons produced and released as a sound cartoon, using the RCA Photophone sound system. The cartoon was produced (and also premiered on September 1, 1928 in NYC) before Disney’s Steamboat Willie (1928), although it was soon overshadowed by Disney's release. |

The Fleischer Brothers: Inventors, and Cartoon Makers at Inkwell Studios

At the same time, serious rivals to Disney's animation production came from the Fleischers (Max, Dave, Joe, and Lou). They were already making technical innovations that would revolutionize the art of animation. In 1915, Max Fleischer invented the rotoscope(patented in 1917) to streamline the frame-by-frame copying process - it was a device used to overlay drawings on live-action film. The Fleischers were also pioneering the use of 3-D animation landscapes, and they produced two versions of The Einstein Theory of Relativity (1923) - a 20-minute documentary short, and a 50-minute feature-length educational version - often considered the first documentary feature-length animation. Another Fleischer exploration of scientific theory (using film and animation) in the same year was Evolution (1923) (aka Darwin's Theory of Evolution).

|  |

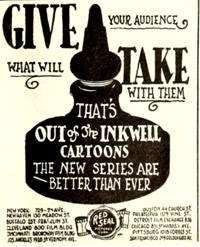

In 1919, one of the Fleischers' first successful ventures was the premiere of the part live-action/part animation Out of the Inkwell series of shorts, featuring their animated Ko-Ko the Clown character in a live-action world - one of the first animated characters.

In 1919, one of the Fleischers' first successful ventures was the premiere of the part live-action/part animation Out of the Inkwell series of shorts, featuring their animated Ko-Ko the Clown character in a live-action world - one of the first animated characters.

After working for John Bray (of Bray Studios/Productions) for two years, the brothers left and formed their own studio in 1921 - dubbed Inkwell Studios (aka Out of the Inkwell, Inc.), and titled their short subjects and animations Out of the Inkwell Films. In 1923 when they expanded, Max founded the Red Seal Distribution Company to circulate their animated films (or cartoons) and shorts. [Note: The Red Seal Company and Out of the Inkwell Films only lasted for a few years until 1928 when they went broke, and Paramount Pictures took over distribution.]

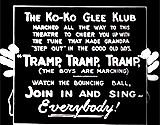

One of their early animation series, featuring Ko-Ko the Clown, was composed of almost 50 short, 3-4 minute films called Ko-Ko Song Car-Tunes (1924-1927). The Ko-Ko Song Car-Tunes were the first animated films (cartoons), some of which featured a synchronized soundtrack (they were the first animated films with sound) - the precursors to karaoke, that used the Lee DeForest Phonofilm 'sound-on-film' process. Reportedly, 19 Song Car-Tunes utilized the Phonofilm sound system (some were first released in a silent version, and then with sound). They were the first talking cartoons - even pre-dating Disney's Steamboat Willie (1928) by a number of years. In total, there were 49 Car-Tune animations. Some were first released as silents, then with sound (noted in red below). The songs in the series ranged from contemporary tunes to old-time favorites.

These were the first audience participation films, with sing-along lyrics and a 'bouncing-ball' helper. The gimmick was a bouncing ball atop the lyrics on screen, to help audiences follow along with the song. Ko-Ko the Clown continued to be their star performer, who often climbed out of an inkwell at the start of each cartoon. One of the first Car-Tune cartoons was Oh, Mabel (1924), that began with Ko-Ko the Clown jumping out of an inkwell and running through a few hijinks before the song Oh, Mabel.

These were the first audience participation films, with sing-along lyrics and a 'bouncing-ball' helper. The gimmick was a bouncing ball atop the lyrics on screen, to help audiences follow along with the song. Ko-Ko the Clown continued to be their star performer, who often climbed out of an inkwell at the start of each cartoon. One of the first Car-Tune cartoons was Oh, Mabel (1924), that began with Ko-Ko the Clown jumping out of an inkwell and running through a few hijinks before the song Oh, Mabel.

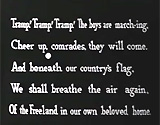

My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean (1925) was reportedly the first cartoon to use the bouncing ball with the lyrics of a song. In My Old Kentucky Home (1926, 1928), the earliest Car-Tune to synchronize the animation with sound, Bimbo spoke to the audience: "Follow the ball and join in everybody." Come Take A Trip in My Airship(released first as a silent film in 1924 and then with sound in 1925 (in the Song Car-Tune Series) and in 1930 (in Fleischer's Screen Songs Series)), acc. to the Guinness Book of Movie Facts and Feats, was the "first cartoon talkie for theatrical release." In Tramp, Tramp, Tramp - The Boys Are Marching (1926, 1928), Ko-Ko held up a sign encouraging the audience in a theatre to "watch the bouncing ball" and sing: "Tramp, Tramp, Tramp."

|  |  |

Title Screen | ||

|  |  |

| 1924: Come Take a Trip in My Airship (1924), Goodbye My Lady Love (1924), Mother, Mother Pin a Rose on Me (1924), Oh, Mabel (1924) |

| 1925: Come Take a Trip in My Airship (1925), The Old Folks At Home (1925), Mother Pin a Rose on Me (1925), I Love a Lassie (1925), Swanee River (1925), East Side, West Side (1925), Daisy Bell (1925), Nutcracker Suite (1925), My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean (1925), Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-A (1925), Dixie (1925),Sailing, Sailing Over the Bounding Main (1925) |

| 1926: Darling Nellie Gray (1926), Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly? (1926), My Old Kentucky Home (1926) (sound in 1928), Beautiful Eyes (1926), Finiculee Fincula (1926), Sweet Adeline (1926), In My Harem (1926), Tramp, Tramp, Tramp - The Boys Are Marching (1926) (sound in 1928), Goodbye My Lady Love (1926), Comin' Thru The Rye (1926), Pack Up Your Troubles (1926), The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1926), By The Light Of The Silvery Moon (1926), In the Good Old Summertime (1926), Oh You Beautiful Doll (1926), The Sheik of Araby (1926), Annie Laurie (1926), Oh, How I Hate to Get Up In the Morning (1926), When I Lost You (1926), Old Black Joe (1926), When The Midnight Choo-Choo Leaves For Alabam' (1926), Oh, What a Pal Was Mary (1926), Everybody's Doing It (1926), Dear Old Pal (aka Old Pal) (1926), Yak-A-Hula-Hick-A-Doola (1926), Margie (1926), My Wife's Gone to the Country (1926) |

| 1927: Oh, Suzanna (1927), Call Me Up Some Rainy Afternoon (1927), The Rocky Road to Dublin (1927), Jingle Bells (1927), Waiting For the Robert E. Lee (1927) |

| 1928: Oh, I Wish I Was in Michigan (1928) |

Ko-Ko's last silent film was Chemical Koko (1929). As with Felix the Cat, the advent of sound seemed to doom Ko-Ko (although he reappeared in the early 1930s). In 1929, Max Fleischer started a new studio on Long Island, named Fleischer Studios, while still in a relationship with Paramount.

The Fleischers: Talkartoons and Betty Boop

The Fleischers launched a new series from 1929 to 1932 called Talkartoons that featured their smart-talking, singing dog-like character named Bimbo. Although Bimbo quickly became a star, and sometimes appeared with a revitalized Ko-Ko the Clown in a supporting role (Ko-Ko last appeared in the Betty Boop talkie cartoon Ha! Ha! Ha! (1934)), Bimbo was soon relegated to a minor co-starring role with the Fleischer's next racy headlining cartoon star, Betty Boop.

The Fleischers launched a new series from 1929 to 1932 called Talkartoons that featured their smart-talking, singing dog-like character named Bimbo. Although Bimbo quickly became a star, and sometimes appeared with a revitalized Ko-Ko the Clown in a supporting role (Ko-Ko last appeared in the Betty Boop talkie cartoon Ha! Ha! Ha! (1934)), Bimbo was soon relegated to a minor co-starring role with the Fleischer's next racy headlining cartoon star, Betty Boop.

Max Fleischer was responsible for the provocative, adult-oriented, cartoon Betty Boop vamp-character, who always wore a strapless, thigh-high gown (and visible garter on her left thigh) and was based on Jazz era singer Helen Kane (although some claimed she resembled flapper icon Clara Bow's 'It' Girl and Mae West).

A prototype of the squeaky- and baby-voiced cartoon queen (voiced for most of the 30s by Mae Questel) was introduced in the 7th Bimbo Talkartoon entitled Dizzy Dishes (1930) - with her appearing un-named as a long-eared puppy dog! She also appeared (again with dog ears) in Talkartoon's and Fleischer's Mysterious Mose (1930) (the cartoon was slightly risque - while shivering with fright, Betty's nightgown jumped up off her body, and when a mysterious figure appeared under a blanket next to her in bed, she rubbed its belly to see if it was real).

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

In the early cartoon Betty Co-Ed (1931), she was called Betty, and in another pre-Code Bimbo cartoon entitled Silly Scandals (1931) (the title spoofed Disney's Silly Symphonies), she was named Betty Boop for the first time but still with puppy dog ears - she sang You're Driving Me Crazy (from the musical comedy Smiles (1930)) while her dress top kept falling down to reveal her lacy bra. In Talkartoons' Any Rags (1932), she was transformed into a human after losing her floppy dog ears (they became hoop earrings), and her nose became button-shaped and flesh-colored. In Stopping the Show (1932), she appeared under her own credits banner for the first time (she had previously appeared only in Talkartoons and Screen Songs).

Betty Boop's voice was modeled on the voice of another actress, Helen Kane, who created a sensation on Broadway in 1928 with a "boop-oop-a-doop" rendition of the hit song I Wanna Be Loved by You. The cartoon character with a high baby voice, large child-like head and eyes, signature wink, fluttering lashes, shimmying body, and spit curls appeared in a series of short cartoons and became the top Fleischer star, with more than 100 films (shorts) in the 1930s:

- Minnie the Moocher (1932) - with live action footage of Cab Calloway And His Orchestra (Calloway's first appearance in a Betty Boop cartoon, and the oldest-known footage of the performer)

- Boop-Oop-A-Doop (1932), considered risque, and featuring the first instance of Betty's theme song: Don't Take My Boop-Oop-A-Doop Away

- Betty Boop's Bamboo Isle (1932) - a pre-Code cartoon in which Betty performed a sexy hula wearing only a grass skirt and floral lei covering bare breasts

- I'll Be Glad When You're Dead You Rascal You (1932) - featuring Koko the Clown, Bimbo, and a guest appearance from Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra (with some of his earliest live footage); also controversial for racial stereotypes

- Snow White (1933) (aka Betty Boop in Snow-White) - (with another appearance by Cab Calloway) - the first animated film based upon the Grimm Brothers' fairy tale

- The Old Man of the Mountain (1933) - criticism of the sexually-suggestive film (with Cab Calloway in his third and last appearance in a Betty Boop cartoon) helped spur Fleischer Studios to tone down Betty Boop's character, and after 1934, she no longer appeared with African-American jazz performers

- Red Hot Mama (1934) - the UK reportedly banned the cartoon because it depicted Hell in a humorous way

- Betty Boop's Rise To Fame (1934) - highlights from three of Betty's popular cartoons: Stopping The Show, Betty Boop's Bamboo Isle (her hula dance), and The Old Man Of The Mountain

- Poor Cinderella (1934) - the Fleischer's first (and sole) Betty Boop color cartoon, with Betty sporting red hair

- Riding the Rails (1938) - Betty appeared with her dog, Pudgy the Pup

Unfortunately, the cute, titillating 'boop-oop-a-doop' Betty with an exposed garter and strapless frock was destined to be censored with the advent of the enforceable, conservative and puritanical Hays Production Code in 1934. The Betty Boop cartoons were stripped of sexual innuendo and her skimpy dresses, and she became more family-friendly. As a result of the drastic changes to her character after 1934, her popularity declined, and her demise came with her last cartoon appearance in Rhythm on the Reservation (1939) - often criticized for its potentially offensive Native-American characterizations. The last official Betty Boop cartoon released was Yip Yip-Yippy (1939), without Betty Boop in it.

[Note: During the 30s, Mae Questel recorded On the Good Ship Lollipop -- in Betty Boop's voice-- which sold more than 2 million copies.]

Fleischer Studios: Popeye

The Fleischers also obtained the rights to the tough, one-eyed, spinach-loving sailor Popeye with over-sized arms (who was introduced in mid-January 1929 in creator Elzie C. Segar's "Thimble Theatre" newspaper comic strip published in the New York Journal for King Features Syndicate, in its 10th year since 1919). Popeye became so popular in the comic strip that it was renamed "Thimble Theatre, Starring Popeye." In 1933, Max Fleischer adapted the Thimble Theatre characters into a series of Popeye the Sailor theatrical cartoon shorts for Paramount Pictures.

The Fleischers also obtained the rights to the tough, one-eyed, spinach-loving sailor Popeye with over-sized arms (who was introduced in mid-January 1929 in creator Elzie C. Segar's "Thimble Theatre" newspaper comic strip published in the New York Journal for King Features Syndicate, in its 10th year since 1919). Popeye became so popular in the comic strip that it was renamed "Thimble Theatre, Starring Popeye." In 1933, Max Fleischer adapted the Thimble Theatre characters into a series of Popeye the Sailor theatrical cartoon shorts for Paramount Pictures.  |  |  |

Popeye first appeared on film alongside established cartoon-star Betty Boop in July, 1933 in Fleischers' Betty Boop Cartoon series titled Popeye the Sailor (1933), in which they danced the hula. Popeye's voice was provided by William Costello (better known as Red Pepper Sam) from 1933-35. [After Costello was dismissed, Jack Mercer, who began his career as an artist at the cartoon studio, provided Popeye's voice and ad-libbed mutterings for the Fleischers until 1957, and various voices for the two Fleischer feature-length animations - see below.]

The same year in September, the first official Popeye cartoon, I Yam What I Yam (1933) was released - the first in a long series of animated shorts. Popeye's first Technicolor cartoon was the two-reel special release Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad the Sailor (1936), noted for its experimental multi-plane 3-D backgrounds, and for being the first Fleischer cartoon to be nominated for an Academy Award - Best Short Subject - Cartoon. The cartoon character became well-known for his theme song (excerpt below):

I'm Popeye the Sailor Man

I'm Popeye the Sailor Man

I'm strong to the finich

'Cause I eats me spinach

I'm Popeye the Sailor Man...

The voices of Olive Oyl, Popeye's whiny girlfriend, and Sweet Pea were provided by Mae Questel. The character Wimpy provided the name for an unpopular type of British hamburger.

By 1938, Popeye had replaced Mickey Mouse as the most popular cartoon character in America. Paramount's Famous Studios continued the series beginning in 1942, and Popeye's movie career lasted until 1957. Robert Altman directed the live-action film flop, Popeye (1980), starring Robin Williams as Popeye, Shelley Duvall as Olive Oyl, and Ray Walston as Pappy, Popeye's father.

Fleischer Studios: Superman

Dave and Max Fleischer, in an agreement with Paramount and DC Comics, also produced a series of seventeen expensive Superman cartoons in the early 1940s. The high-budgeted films were at $100,000 an episode, about four times the average price of comparative cartoons.

|  |  |

The Fleischers were responsible for the first ten Superman cartoons (up through Japoteurs (1942)), with the remaining shorts produced by Paramount's Famous Studios during 1942-43. [Note: The recognizable theme song for the series was incorporated into John Williams' score for Superman: The Movie (1978), and the cartoons were referenced in The Iron Giant (1999).]

The Fleischers were responsible for the first ten Superman cartoons (up through Japoteurs (1942)), with the remaining shorts produced by Paramount's Famous Studios during 1942-43. [Note: The recognizable theme song for the series was incorporated into John Williams' score for Superman: The Movie (1978), and the cartoons were referenced in The Iron Giant (1999).]

The first 10 minute Superman short, Superman (1941), which premiered in 1941, introduced the narrator's exclamations of "faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound!" It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Subject, but lost to Disney'sLend a Paw (1941). The most famous of the series was the second entry, The Mechanical Monsters (1941) with the super-hero battling giant flying robots. It also included a redesigned, more sensual Lois Lane and marked the first time that Superman would change into his classic red and blue costume in a telephone booth. It was also the only time that Superman was shown using X-ray Vision in a Fleischer short. Also notable was The Bulleteers (1942), the fifth entry of the 17 shorts. In the story, the Daily Planet's Clark Kent/Superman battled and eliminated a gang in Metropolis known as The Bulleteers - named after their bullet-shaped rocket car.

Fleischer Studios: Two Feature Films

The Fleischers were in direct competition with Disney. Two feature-length animations with whimsical characters and advanced animation techniques by the Fleischers deserve mention, although the Fleischers are better-remembered for their shorts than for their only two features:

| Title Screen | Title (Year) | Notable: |

|

| |

|

|

As a final footnote, the struggling and insolvent Fleischer Studios was acquired by Paramount Pictures in 1942. The studio was restructured and renamed Famous Studios, and returned to New York after being in Florida since 1938. Work continued on the Popeye and Superman series.

The studio also produced cartoons based on Harvey Comics characters, including over two dozen Little Lulu (Moppet) cartoons in the 40s, and over 50 Casper the Friendly Ghost cartoons that stretched into the 1950s (Casper made his debut in Izzy Sparber's cartoon short The Friendly Ghost (1945)).

[Little-known fact: Max Fleischer was the father of Richard Fleischer, the director of Disney's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Fantastic Voyage (1966), Doctor Dolittle (1967) and Soylent Green (1973).]

______________________________________________________

Walt Disney's Silly Symphonies:

Beginning in the 1930s, feature films were often preceded by obligatory cartoon shorts, showcasing a rapidly-developing film technique. While working on the development of Mickey Mouse shorts, Disney also began a new venture - called Silly Symphonies - an ambitious, innovative and groundbreaking series of stand-alone animations with musical accompaniment.

He used the series of 75 shorts (that lasted 10 years from 1929 until 1939) to experiment with different processes, techniques, characters, stories, and technologies to be later used in his full-length feature animations. They won a total of seven Academy Awards for Best Animated Short Subject (see chart below). There were numerous imitators, including Warner Bros' Merrie Melodies (see below).

A Selection | ||

| Title Screen | Title (Year) | Notable: |

|

| |

| Springtime (1929) Hell's Bells (1929) The Merry Dwarfs (1929) |

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Other Disney Cartoon Characters:

The cartoon character Pluto was first introduced (unnamed) in 1930 in the Mickey Mouse cartoon The Chain Gang (1930) and named Rover (Minnie Mouse's dog) in The Picnic (1930). It took another Mickey Mouse short, The Moose Hunt (1931) before he attained his familiar name. The 1931 cartoon was also famous for having Pluto's only spoken line of dialogue - to Mickey: "Kiss." Eventually, Lend a Paw (1942), with Pluto in the lead role, won an Oscar for Best Short Subject: Cartoon. Goofy debuted as an extra in Mickey's Revue (1932). [Recently, he was featured in his own full-length film, A Goofy Movie (1995).]

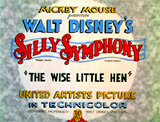

A sailor-suited, web-footed Donald Duck was introduced in 1934 in Silly Symphony's The Wise Little Hen (1934) (with his brief opening words "Who--me? Oh no! I got a bellyache!"), and then in Orphan's Benefit (1934) (this also marked Donald's firstappearance in a Mickey Mouse cartoon, and with Goofy - of course, this was the first time that all three characters appeared together). Mickey Mouse (and Minnie Mouse) first appeared together for their screen debut in Steamboat Willie (1928), but Mickey's official debut was in The Band Concert (1935) (made in color). Donald's female partner, Daisy (first named "Donna Duck") was introduced in Don Donald (1937), and made her first official appearance (speaking like Donald) in Mr. Duck Steps Out (1940).

The Chain Gang (1930)Pluto (unnamed) a yellow-orange color, medium-sized, short-haired bloodhound dog with black ears |  The Moose Hunt (1931)Pluto(named for the first time) |  Mickey's Revue (1932) Goofy a tall, anthropomorphic black dog with a Southern drawl, who typically wore a turtle neck and vest, with pants, shoes, white gloves, and a tall hat |

The Wise Little Hen (1934)Donald Duck an anthropomorphic white duck with a yellow-orange bill, legs, and feet, who typically wore a sailor shirt and cap with a bow tie |  Don Donald (1937)Daisy Duck (known as "Donna") a white duck with an orange bill, legs, and feet; she usually had sultry lavender eye shadow, long distinct eyelashes, and a skirt of ruffled feathers; also with a V-necklined blouse, a head bow matching her heeled shoes and a single bangle on her wrist |  Mr. Duck Steps Out (1940) Daisy Duck (first official appearance) |

Columbia Pictures Cartoons: Krazy Kat

Columbia Pictures became involved in the world of animated films when the studio began distributing Mickey Mouse and other shorts from The Walt Disney Studios. Even before it set up its own animation studio in 1934, it had been producing a long-running series of black and white cartoons, beginning in 1929 (in 1935 they became Technicolored), featuring the character of Krazy Kat. Krazy Kat was based on the 1913 newspaper comic by George Herriman, that ran until 1944 when the comic artist died. In particular, several of the IFS/Bray Krazy shorts in the first few years of Krazy Kat's appearances in cartoons were adapted from comic strips.

Columbia Pictures became involved in the world of animated films when the studio began distributing Mickey Mouse and other shorts from The Walt Disney Studios. Even before it set up its own animation studio in 1934, it had been producing a long-running series of black and white cartoons, beginning in 1929 (in 1935 they became Technicolored), featuring the character of Krazy Kat. Krazy Kat was based on the 1913 newspaper comic by George Herriman, that ran until 1944 when the comic artist died. In particular, several of the IFS/Bray Krazy shorts in the first few years of Krazy Kat's appearances in cartoons were adapted from comic strips.

Krazy Kat, of an ambiguous gender, was an obstinate black cat who had an infatuation for his evil rival, Ignatz Mouse (who often threw bricks at Krazy). The third component of a love triangle was a dog named Offissa Bull Pupp, a police officer. Over the years, Krazy more and more resembled the more popular Felix the Cat and later, Mickey Mouse.

Krazy Kat - Bugologist (1916) |  Love's Labor Lost (1920) |  Searching for Santa! (1925) |  Ratskin (1929) |

(1916 – 1917) 26 Theatrical Cartoons | (1920 – 1921) 10 Theatrical Cartoons | (1925 – 1929) 99 Theatrical Cartoons | (1929 - 1939) 97 Theatrical Cartoons |

The cartoon Kat had been established as early as 1916 by Hearst's International Film Service, Inc. with their Introducing Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse (1916). In 1918, Krazy Kat was acquired by Bray's Goldwyn-Bray Pictographs until 1921. Then, after a short break, Winkler Pictures took over from 1925 until 1929, and then Columbia acquired the series. Columbia Pictures' first Krazy Kat cartoon (the first one released with sound) was Ratskin (1929), followed by Canned Music (1929), while Columbia's last Krazy Kat cartoon was Krazy's Shoe Shop (1939).

Terry Toons:

After leaving Fables Studio (created by newspaper cartoonist Paul Terry in 1921 for his Aesop's Film Fables series), Terry set up his own Terry Toons animation studio in New Rochelle, NY in 1929. [Note: The Fables Studio was renamed Van Beuren Studios in 1929.] Terry (as producer/writer) and partner Frank Moser (as director) began producing cartoons by 1930 (until 1935) that were first distributed by Fox Pictures, and then by Paramount Pictures. The early cartoons that came from the "budget" studio were cheapy made and rushed to print, and the studio was infamously known for resisting the new technologies of sound and color.

The titles of their first 25 films in the early 1930s were all food items, such as: Caviar (1930), Pretzels (1930), Spanish Onions (1930), Indian Pudding (1930), Roman Punch (1930), Hot Turkey (1930) - and many more.

Their first star in the 1930s was Farmer Alfalfa, a familiar grizzly-farmer character that had appeared in some of Paul Terry's earlier cartoons (in Bray Studios from 1916-1923 and for the Aesop's Film Fables series from 1922-1929), and now reappeared in Terry Toons' cartoons (a major period from 1930-1937). His first Terry Toons cartoons were French Fried (1930) and Golf Nuts (1930). Among others, four additional minor cartoon series (with new characters) were also released in the mid-to-late 1930s:

- 13 Puddy the Pup cartoons (from 1935-1942) - a white dog with a black eye patch, who first appeared in The Bullfight (1935)

- 10 Kiko the Kangaroo cartoons (from 1936-1937) - a fun-loving, mischievous marsupial who appeared first in a Farmer Alfalfa cartoon, The Prize Package (1936)

- 48 Gandy Goose cartoons (from 1938-1955), a goose that sounded like comic actor Ed Wynn, first seen in Gandy the Goose (1938)

- Sour Puss cartoons, about 2 1/2 dozen titles (from 1939-1955), a cantankerous Jimmy Durante-like cat, first appearing in The Owl and the Pussycat (1939), and first paired with Gandy the Goose in G-Man Jitters (1939)

Puddy the Pup |  Kiko the Kangaroo |  Gandy Goose |  Sour Puss |

Terry Toons had to wait until the 1940s to really find success. The most famous and valuable cartoon character from Terry Toons (and 20th Century Fox) was Mighty Mouse, a Superman-like mouse superhero that first debuted as a prototype "Super Mouse" in the short The Mouse of Tomorrow (1942).

Mighty Mouse and Heckle & Jeckle | |||

|  | ||

The Mouse of Tomorrow (1942) |  The Wreck of the Hesperus (1944) |  The Talking Magpies (1946) |  Messed Up Movie Makers (1966) |

In a couple of years, the more recognizable Mighty Mouse was born and renamed properly in an appearance in his 8th film, The Wreck of the Hesperus (1944). He became known for his yellow costume, red cape, and his anthem song, with the words "Here I come to save the day!" Ultimately, Mighty Mouse appeared in 80 theatrical films between 1942 and 1961. Later, CBS-TV took the Mighty Mouse cartoons and packaged them into a very popular Saturday morning television show called Mighty Mouse Playhouse,beginning in late 1955 and lasting for a record eleven years until 1967. Mighty Mouse was the first cartoon character ever to appear on Saturday mornings.

In a couple of years, the more recognizable Mighty Mouse was born and renamed properly in an appearance in his 8th film, The Wreck of the Hesperus (1944). He became known for his yellow costume, red cape, and his anthem song, with the words "Here I come to save the day!" Ultimately, Mighty Mouse appeared in 80 theatrical films between 1942 and 1961. Later, CBS-TV took the Mighty Mouse cartoons and packaged them into a very popular Saturday morning television show called Mighty Mouse Playhouse,beginning in late 1955 and lasting for a record eleven years until 1967. Mighty Mouse was the first cartoon character ever to appear on Saturday mornings.

The other most famous of Terry Toons characters were Heckle & Jeckle, two identical black, large yellow-billed, wise-cracking crows (or magpies) who first appeared in the mid-40s in Paul Terry's The Talking Magpies (1946). Their debut appearance was actually in a Farmer Alfalfa cartoon, where the pair were depicted as a squabbling married couple. Their last animated cartoon theatrical film appearance was in Messed Up Movie Makers (1966), their 52nd short.

Leon Schlesinger: The Early Days at Warners and the Character of Bosko

Warners' producer of cartoons, Leon Schlesinger (from 1930-1944) (and Leon Schlesinger Productions) released a 5-minute pilot film named Bosko The TalkInk Kid (1929) - the first synchronized talking animated short/cartoon (as opposed to a cartoon with a soundtrack), with a little black boy character named Bosko who actually spoke dialogue. The Bosko pilot was drawn by two ex-Disney animators -- Hugh Harman (1903-1982) and Rudolf Ising (1903-1992), who along with animator Friz Freleng, produced and directed the first cartoons for Warner Bros.

Warners' producer of cartoons, Leon Schlesinger (from 1930-1944) (and Leon Schlesinger Productions) released a 5-minute pilot film named Bosko The TalkInk Kid (1929) - the first synchronized talking animated short/cartoon (as opposed to a cartoon with a soundtrack), with a little black boy character named Bosko who actually spoke dialogue. The Bosko pilot was drawn by two ex-Disney animators -- Hugh Harman (1903-1982) and Rudolf Ising (1903-1992), who along with animator Friz Freleng, produced and directed the first cartoons for Warner Bros.

In the pilot, Rudolf Ising sat at his drawing board and sketched the character of Bosko, an African-American boy that interacted with him. At the end of the cartoon, just before Bosko was sucked back into the inkwell, he said, "Well, so long, folks! See yah all later!" - the origination of the later famous "That's all, folks!" end title. The Bosko pilot short was the impetus for the birth of Warner Bros.' Looney Tunes (see more below).

[Note: The character of Bosko slightly resembled its major competitor at the time - Disney's Mickey Mouse. Many of the studios also had similar characters, such as Lantz' Oswald the Lucky Rabbit (see above) or Columbia's Krazy Kat, and even Warners' Beans the Cat. Also, Bosko was a cartoonish adaptation of Al Jolson’s character in The Jazz Singer (1927).]

The Ascendancy of Warner Bros:

Looney Tunes

Opening Screen |  Sinkin' in the Bathtub (1930) |  Bosko: "That's all, folks!" |

The earliest talking 'Looney Tune' was the black and white comedy short Sinkin' in the Bathtub (1930), released on May 30, 1930. It again featured Bosko in the starring role, and also included the song later popularized by Tiny Tim: "Tiptoe Through the Tulips." And it was notable as the first non-Disney animated cartoon with a pre-recorded soundtrack (like the pilot), seen with synchronized speech and dancing. Unfortunately, Bosko's character helped contribute to the accusation that racial and ethnic stereotypes were being promoted. Bosko ended the film with the first spoken instance of "That's all, folks!"

Ultimately, Bosko was the star of over three dozen Looney Tunes shorts released by Warner Bros. from 1930-1933. His final Looney Tunes WB cartoon was Bosko's Picture Show (1933) - the first film to target Hitler. Controversy plagued the short in one scene, when Bosko shouted out what seemed to be a profanity ("The dirty f--k!"), although the swear word could have been "fox" or "mug." Some interpreted it as Harman's and Ising's farewell to Warner Bros' chief Schlesinger when they departed for MGM (see more below).

Ultimately, Bosko was the star of over three dozen Looney Tunes shorts released by Warner Bros. from 1930-1933. His final Looney Tunes WB cartoon was Bosko's Picture Show (1933) - the first film to target Hitler. Controversy plagued the short in one scene, when Bosko shouted out what seemed to be a profanity ("The dirty f--k!"), although the swear word could have been "fox" or "mug." Some interpreted it as Harman's and Ising's farewell to Warner Bros' chief Schlesinger when they departed for MGM (see more below).

Merrie Melodies

Following their success with Looney Tunes in the early 1930s, Warners expanded with a lively new series called Merrie Melodies (produced by Leon Schlesinger, and also headed up by Harman and Ising, although assisted by Bob Clampett). The original idea for the new Merrie Melodies cartoon series was to feature music from the soundtracks of current Warner Bros. films, without recurring characters.

The first three Merrie Melodies introduced a mouse-like male character named Foxy, created by animator Rudy Ising. The first Merrie Melodie was Lady, Play Your Mandolin! (1931), released on August 31, 1931. The second and third shorts were Smile, Darn Ya, Smile! (1931) (animated by Isadore Freleng & Max Maxwell) and One More Time (1931) (Foxy's last cartoon appearance). At the end of each of the three shorts, Foxy came out from behind a bass drum and said to viewers: "So long, folks!" - another example of the familiar ending: "That's all folks!" The Merrie Melodies were mildly popular, and even achieved an Academy Award nomination in their second year for the cat-and-mouse tale It's Got Me Again! (1932) - it became the first Warner Bros. cartoon nominated for an Academy Award.

Harman-Ising Cartoon Production | |||

Foxy: "So long, folks!" |  Lady, Play Your Mandolin! (1931) |  Smile, Darn Ya, Smile! (1931) |  One More Time (1931) |

Competition from MGM:

Happy Harmonies (1934-1938)

Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies were made with Harman-Ising until near mid-1933, but then there was a major change when they split with Schlesinger Productions and Warner Bros. and ventured off to MGM. Harman and Ising took with them the copyrights to their characters and cartoons.

Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies were made with Harman-Ising until near mid-1933, but then there was a major change when they split with Schlesinger Productions and Warner Bros. and ventured off to MGM. Harman and Ising took with them the copyrights to their characters and cartoons.

By 1934 at MGM, Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising had created a new Happy Harmonies series of cartoons, eventually producing a total of 37 films in the series by 1938. The last Happy Harmonies short was The Little Bantamweight (1938).

Some of the early shorts in the series again starred the character of Bosko, who was soon modified to resemble an African-American boy:

- The Discontented Canary (1934) - the first MGM cartoon

- The Old Pioneer (1934) - the first title named with the Happy Harmonies label

- A Tale of the Vienna Woods (1934)

- Bosko's Parlor Pranks (1934) - the first appearance of Bosko in a color cartoon

- Toyland Broadcast (1934)

- Hey-Hey Fever (1935) - the last appearance of the original Bosko before modification

- Run, Sheep, Run! (1935) - the first appearance of the new Bosko

- Circus Daze (1937) - the last short with the Happy Harmonies label

- Little Ol' Bosko in Bagdad (1938) - the last Bosko cartoon short

The Reinvention of Warner Bros.

From 1933-1935, Warner Bros. was forced to invent and introduce new characters for its future cartoons - Buddy, Beans the Cat, Porky, twin singing puppies Ham and Ex, Little Kitty, and Oliver Owl (see more below), hoping that one or more of them would stand out and become popular. Producer Leon Schlesinger began assembling more staff for Warners, including Friz Freleng and Disney animator Jack King (famous for The Three Little Pigs) to begin creating new Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series. Friz Freleng headed the Merrie Melodies productions, while Jack King took over the Looney Tunes series.

1933  Opening Title - 1933  Buddy's Day Out (1933)  "Buddy" Our Hero  Buddy: "That's all, folks!" Buddy: "That's all, folks!" |  1935 1935 Opening Title - 1935 Opening Title - 1935   Buddy the Gee Man (1935)  Buddy: "That's all, folks!" Buddy: "That's all, folks!" |  1935 1935 Opening Title - 1935 Opening Title - 1935 A Cartoonist's Nightmare (1935)  Beans: "That's all, folks!" |  1936  Opening Title - 1936 Opening Title - 1936 Westward Whoa (1936)  Ending Title Screen Ending Title Screen |

For a couple of years, Looney Tunes were forced to rely on a new main character - Buddy, a Bosko-like young boy character. The firstLooney Tune cartoon to feature Buddy was Buddy's Day Out (1933), followed quickly by a number of others (from 1933-1935). At the end of the cartoons, Buddy would wave and say: "That's all, folks!"

- Buddy's Beer Garden (1933), Buddy's Show Boat (1933), Buddy the Gob (1934) (the first supervised by Friz Freleng), Buddy and Towser (1934), Buddy's Garage (1934), Buddy's Trolley Troubles (1934), Buddy of the Apes (1934), Buddy's Bearcats (1934), Buddy's Circus (1934), Buddy the Detective (1934), Viva Buddy (1934) (with a surprise appearance by the four Marx Bros.), Buddy the Woodsman (1934), Buddy's Adventures (1934), Buddy the Dentist (1934), Buddy's Theatre (1935), Buddy's Pony Express (1935), Buddy of the Legion (1935) (Chuck Jones received his first credit as animator of a Warner Bros. cartoon), Buddy's Lost World (1935), Buddy's Bug Hunt (1935), Buddy in Africa (1935), Buddy Steps Out (1935), and Buddy the Gee Man (1935) - the last Buddy cartoon

However, a new popular character began to emerge - Beans the Cat, a "Mickey Mouse-like" feline whose first solo appearance was in the next film in the series: A Cartoonist's Nightmare (1935). Beans ended his first film with the same familiar farewell: "That's all folks!" As Beans' popularity decreased within a year or two, he was soon to be supplanted by the character of his supporting co-star Porky Pig. Beans' last cartoon (and his last short with Porky and puppies Ham and Ex) was Looney Tunes' Westward Whoa (1936) - it marked the last appearance of Porky in the "Beans" series.

During this time, the first color (Cinecolor, not Technicolor) WB Merrie Melodies was released, Honeymoon Hotel (1934). WB's first three-strip Technicolor short was Flowers for Madame (1935).

The Classic Warners' Cartoon Characters:

Beginning in 1935, Warners' hired a new third full-time director of animation, Fred 'Tex' Avery who was recruited from Lantz (see more below) to join Jack King and Friz Freleng. The trio would soon be creating some of the best-loved cartoon characters and animations of all time. They worked in a run-down back lot building known as 'Termite Terrace.' Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies produced cartoons that directly imitated or copied their major competitor, Disney's Silly Symphonies. Animators at Warner Bros. studios began to challenge the style, form and creative content of Disney's pastoral animations in the early 1930s and after. Their cartoons were characterized as being more hip, adult-oriented, and urban than the comparable Disney cartoons of the same period. They also came up with innovations in their cartoons, such as their first full-color Looney Tune short The Hep Cat (1942).

The Merry Melodies' two-strip (red-green) Technicolored I Haven't Got a Hat (1935), directed by Isadore Freleng, featured a number of anthropomorphic animals, including Beans the Cat and a secondary stuttering character known as Porky Pig (in his film debut). This short launched Porky Pig's career. Bob Clampett was also involved with the animation team - his first screen credit was for the Freleng-directed Shake Your Powder Puff (1934), and he played a role in the creation and development of the cartoon characters of Porky Pig (and later Bugs).

Avery's first WB cartoon created with the 'Termite Terrace' unit was Looney Tunes' Gold Diggers of '49 (1935) featuring Beans the Cat (in his third appearance), and also starring Porky Pig (redesigned) in his second short. As his popularity declined, Beans the Cat was gradually being replaced by Porky, and completely disappeared in 1936.

The first cartoon in the Porky Pigs series was Looney Tunes' Plane Dippy (1936), with a short final cameo by Beans. The very pig-like Porky was again redesigned by Avery in his fourth directed film featuring Porky, now made to look more cartoonish (smaller and rounder) in Looney Tunes' Porky the Rain-Maker (1936), notable for having an off-screen narrator. Porky's first appearance with Daffy Duck was in Porky's Duck Hunt (1937), when Mel Blanc took over his voice. And Porky first encountered an early version of Bugs Bunny in Porky's Hare Hunt (1938). In Looney Tunes' Porky in Wackyland (1938), Porky hunted the last elusive and zany Do-Do bird in Wackyland, populated with surrealistic, Salvador Dali-inspired characters. [Note: The cartoon was remade eleven years later (in Cinecolor) and released as a Merrie Melodies short, Dough For The Do-Do (1949).]

1935 Warner Bros. Productions Title Screen  1935 Merrie Melodies' Title Screen |  1935 Warner Bros. Productions Title Screen 1935 Warner Bros. Productions Title Screen 1935 Looney Tunes' 1935 Looney Tunes'Title Screen |  1936 Warner Bros. Productions Title Screen  1936 Looney Tunes' 1936 Looney Tunes'Title Screen |  1938 WB-Vitaphone Opening Title Screen  Looney Tunes' Title Screen |

I Haven't Got a Hat (1935)    1935 Ending Screen: 1935 Ending Screen:"That's all, folks!" |  Gold Diggers of '49 (1935)   1935 Ending Screen - Beans: "That's all, folks!" |  Porky the Rain-Maker (1936)  Ending Title Screen |  Porky in Wackyland (1938)  1938 Ending Screen - Porky: "(Ble, ble, ble) That's all, folks!" |

From 1935 onward until the early 40s, Avery was responsible for much of the manic, satirical, absurdist, extra-violent, crude characters and corny gags and slapstick of numerous productions. Avery's animations, often designed for adult audiences, were often noted for 'pushing the envelope' of acceptable taste.

Looney Tunes became known for closing with the familiar Porky Pig end tag: "That's All Folks!" In 1936, composer Carl W. Stalling (who was the musical director of Warners' animation department for over two decades) chose "Merrily We Roll Along" (used most often for Merrie Melodies) and "The Merry-Go-Round Broke Down" (used most often for Looney Tunes) as the distinctive theme songs for Warners' cartoons.

Looney Tunes became known for closing with the familiar Porky Pig end tag: "That's All Folks!" In 1936, composer Carl W. Stalling (who was the musical director of Warners' animation department for over two decades) chose "Merrily We Roll Along" (used most often for Merrie Melodies) and "The Merry-Go-Round Broke Down" (used most often for Looney Tunes) as the distinctive theme songs for Warners' cartoons.

Warners' New Animated Characters: Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny

Along with his famed animating staff - Friz Freleng, Bob Clampett and Chuck Jones, Tex Avery created two more of the greatest stars for Warners: Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny (with his famous catchphrase: "What's up, Doc?") (Through most of these years, voice artist Mel Blanc provided the voice for all the starring WB characters: Bugs Bunny, Sylvester the Cat, Porky Pig, Daffy Duck, Yosemite Sam, Speedy Gonzalez, and many others.)

Porky's Duck Hunt (1937) |  Porky's Hare Hunt (1938) |  Daffy Duck & Egghead (1938) |  You Ought To Be in Pictures (1940) |

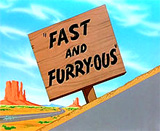

Daffy Duck's first appearance was in Tex Avery's Looney Tunes' Porky short, Porky's Duck Hunt (1937) (Bob Clampett animated the crucial scenes), remade the next year as Looney Tunes' Porky's Hare Hunt (1938). The name Daffy Duck (derived from the name of famed baseball player Dizzy Dean's brother Daffy) was used for the first time in the title of Avery's second, remade Merrie Melodies'duck-hunt picture Daffy Duck & Egghead (1938) - this was also the first Daffy Duck cartoon in color. [Note: Egghead was the prototype for the character of Elmer Fudd - see below.] The black and white Looney Tunes' You Ought To Be in Pictures (1940)directed by Friz Freleng was a hybrid live-action/animated spoof satire of emerging, fast-talking, trouble-making star Daffy who convinced Porky to quit his job at Warners by ending his cartoon contract with studio head Leon Schlesinger.